intro

A database schema represents the logical blueprint and structural framework that defines how data is organized, stored, and accessed within a database system. This comprehensive data architecture serves as the foundation for all database operations, establishing the rules, relationships, and constraints that govern information storage. The schema acts as a metadata layer that describes the entire database structure, including tables, columns, data types, indexes, views, stored procedures, and the intricate relationships between different data elements.

In essence, the database schema functions as an architectural plan that database administrators and developers use to construct and maintain efficient data storage systems. This schema definition encompasses not only the physical arrangement of data but also the logical groupings and conceptual relationships that make the database meaningful for business operations. Modern database management systems rely heavily on well-designed schemas to ensure data integrity, optimize query performance, and maintain consistency across complex data models.

The importance of a properly structured database schema cannot be overstated in today's data-driven environment. Organizations dealing with vast amounts of information require robust schema architecture to handle their data effectively. The schema serves multiple critical functions: it enforces data validation rules, maintains referential integrity between related tables, provides a clear roadmap for application development, and enables efficient data retrieval through optimized query paths. Furthermore, a well-designed schema facilitates collaboration among development teams by providing a standardized framework that all stakeholders can understand and work with effectively.

Why is a Well-Defined Data Schema Crucial for Your Business?

A well-defined data schema forms the backbone of successful business operations in the digital age. Organizations that invest time and resources in developing comprehensive database architecture experience significant advantages in data management efficiency, system performance, and overall operational excellence. The schema structure directly impacts how quickly applications can retrieve and process information, ultimately affecting user experience and business productivity. Companies with optimized database designs report faster query execution times, reduced storage costs, and improved data quality across their systems.

Business intelligence and analytics capabilities depend heavily on the underlying data model quality. A properly structured schema enables organizations to extract meaningful insights from their data, supporting informed decision-making at all levels. The database framework provides the foundation for reporting systems, dashboards, and analytical tools that executives rely on for strategic planning. When the schema design aligns with business processes and reporting requirements, organizations can quickly adapt to changing market conditions and identify new opportunities for growth and optimization.

Data consistency and integrity represent fundamental requirements for regulatory compliance and operational reliability. A well-implemented database schema enforces business rules at the data layer, preventing invalid entries and maintaining referential integrity across related datasets. This systematic approach to data organization reduces errors, minimizes data duplication, and ensures that all departments work with consistent, accurate information. The schema management process also facilitates audit trails and compliance reporting, essential features for businesses operating in regulated industries.

What are the Key Components of a Database Structure?

The fundamental components of a database structure work together to create a cohesive system for data storage and retrieval. Tables serve as the primary containers for data, organizing information into rows and columns that represent entities and their attributes. Each table within the database system corresponds to a specific business entity, such as customers, products, or transactions, with clearly defined boundaries and purposes. The relationship between these tables forms the relational aspect of database architecture, enabling complex queries that span multiple data sources.

Constraints and rules embedded within the schema definition ensure data quality and consistency throughout the database. These include primary key constraints that guarantee unique identification of records, foreign key constraints that maintain referential integrity between related tables, and check constraints that validate data against specific business rules. Additional components such as indexes improve query performance by creating optimized access paths to frequently searched data, while triggers automate responses to specific database events, maintaining data synchronization and implementing complex business logic.

Tables, Fields, and Data Types Explained

Tables represent the foundational building blocks of any relational database structure, organizing data into a structured format that facilitates efficient storage and retrieval. Each table consists of rows (records) and columns (fields), where rows represent individual instances of an entity and columns define the attributes or properties of that entity. The design of tables requires careful consideration of normalization principles to minimize redundancy while maintaining data integrity. Database designers must balance the need for normalized structures with performance requirements, sometimes deliberately introducing controlled redundancy through denormalization to optimize query performance in specific scenarios.

Fields within tables must be carefully defined with appropriate data types that match the nature of the information being stored. The selection of data types impacts storage efficiency, query performance, and data validation capabilities. Each field can have additional properties such as nullability (whether the field can contain null values), default values, and constraints that enforce business rules at the database level. The precision and scale of numeric fields, the maximum length of character fields, and the format of date-time fields all require thoughtful consideration during the schema design process.

Common Data Types in SQL

SQL databases offer a comprehensive range of data types to accommodate various information storage requirements. Numeric data types include INTEGER for whole numbers, DECIMAL and NUMERIC for precise decimal values commonly used in financial calculations, and FLOAT or REAL for approximate numeric values suitable for scientific computations. Character data types such as VARCHAR provide variable-length text storage, while CHAR offers fixed-length storage for standardized codes or identifiers. The TEXT data type handles large text blocks, essential for storing documents, descriptions, or user-generated content within the database system.

Temporal data types play a crucial role in tracking time-sensitive information within database structures. DATE stores calendar dates, TIME captures time values, and DATETIME or TIMESTAMP combine both date and time information with varying levels of precision. Modern database systems also support specialized data types such as JSON for semi-structured data, XML for hierarchical information, BLOB for binary large objects like images or files, and spatial data types for geographic information systems. Understanding the nuances of each data type enables developers to create efficient schema designs that optimize storage space and query performance.

Choosing Appropriate Field Names

Field naming conventions significantly impact the maintainability and usability of database schemas. Clear, descriptive field names that follow consistent patterns make the database structure self-documenting and reduce the learning curve for new team members. Best practices include using lowercase letters with underscores for separation (snake_case), avoiding reserved SQL keywords, and maintaining consistent suffixes for common field types such as '_id' for primary keys and '_date' for temporal fields. The naming strategy should reflect business terminology while remaining technically accurate, creating a bridge between business requirements and technical implementation.

Understanding Primary Keys, Foreign Keys, and Relationships

Primary keys serve as the unique identifier for each record within a table, ensuring that every row can be distinctly referenced and retrieved. The selection of primary keys requires careful consideration of uniqueness, stability, and performance characteristics. While natural keys derived from business attributes can provide meaningful identification, surrogate keys (typically auto-incrementing integers or UUIDs) often offer better performance and flexibility. Composite primary keys, consisting of multiple columns, may be necessary when no single column provides unique identification, though they can complicate relationship management and query construction.

Foreign keys establish referential integrity between related tables, creating the foundation for relational database architecture. These constraints ensure that relationships between entities remain valid by preventing orphaned records and maintaining data consistency across the database system. Foreign key implementation involves careful consideration of cascade options for updates and deletions, determining how changes to parent records affect related child records. The proper use of foreign keys transforms a collection of isolated tables into an integrated database structure that accurately models real-world relationships and business processes.

One-to-One vs. One-to-Many vs. Many-to-Many Relationships

One-to-one relationships occur when each record in one table corresponds to exactly one record in another table, typically used for extending entities with optional or specialized attributes. This relationship pattern often emerges when separating frequently accessed core data from less commonly used supplementary information, improving query performance for common operations. Implementation usually involves sharing primary keys between tables or using a unique foreign key constraint, ensuring the one-to-one correspondence is maintained at the database level.

One-to-many relationships represent the most common pattern in database design, where a single record in a parent table can relate to multiple records in a child table. This relationship models hierarchical structures such as customers with multiple orders, departments with multiple employees, or categories with multiple products. The implementation involves placing a foreign key in the child table that references the primary key of the parent table, creating a clear ownership structure that supports efficient data navigation and aggregation queries.

Many-to-many relationships require an intermediate junction table (also called a bridge or associative table) to properly model complex associations between entities. This pattern appears in scenarios such as students enrolled in multiple courses, products belonging to multiple categories, or users assigned to multiple roles. The junction table contains foreign keys referencing both related entities, often with additional attributes describing the relationship itself, such as enrollment dates or assignment priorities. Proper indexing of junction tables is crucial for maintaining query performance when navigating these complex relationships.

What is the Difference Between a Database Schema and a Database Instance?

The distinction between a database schema and a database instance represents a fundamental concept in database management. The schema defines the structure and organization of the database, acting as a blueprint that specifies tables, columns, relationships, and constraints. This structural definition remains relatively stable over time, changing only through deliberate schema evolution processes. The schema exists as metadata within the database system, describing how data should be organized rather than containing the actual data itself. Database administrators and developers work primarily with the schema during the design and development phases, establishing the framework that applications will use to store and retrieve information.

A database instance, conversely, represents the actual data stored within the database at a specific point in time. This includes all the records, values, and content that populate the tables defined by the schema. The instance changes constantly as users insert, update, and delete records through normal business operations. While the schema might define a customer table with specific columns, the instance contains the actual customer records with their specific values. Multiple instances can exist for a single schema, such as development, testing, and production environments, each containing different data while maintaining the same structural definition.

Data Modeling: The Foundation of Database Architecture

Conceptual Data Models: The Big Picture

Conceptual data models provide a high-level, technology-independent view of the data architecture that focuses on business entities and their relationships. This abstraction level enables stakeholders from various backgrounds to understand and contribute to the database design process without requiring deep technical knowledge. The conceptual model captures the essential business concepts, rules, and relationships that the database must support, serving as a communication tool between business analysts, domain experts, and technical teams. By starting with a conceptual model, organizations ensure that their database structure aligns with business objectives and accurately represents real-world processes.

The development of conceptual data models involves identifying key business entities, defining their essential attributes, and establishing the relationships that connect them. This process requires close collaboration with business stakeholders to understand organizational processes, data requirements, and business rules. The resulting model uses business terminology rather than technical jargon, making it accessible to non-technical team members who must validate that the model accurately represents their domain. Entity-relationship diagrams often visualize conceptual models, using simple shapes and lines to represent entities and their associations without delving into implementation details.

How to Create a Conceptual Schema from Business Requirements

Creating a conceptual schema from business requirements begins with comprehensive requirements gathering through stakeholder interviews, process documentation review, and analysis of existing systems. This discovery phase identifies the key entities that the business works with, such as customers, products, orders, and employees, along with the critical attributes that define each entity. Business analysts must understand not only what data needs to be stored but also how it will be used, including reporting requirements, regulatory constraints, and performance expectations. The requirements gathering process should document business rules that govern data relationships and constraints, ensuring these rules are properly reflected in the conceptual model.

The transformation of business requirements into a conceptual schema involves several iterative steps of refinement and validation. Initial entity identification leads to relationship discovery, where the connections between entities are mapped and characterized. Each relationship must be examined for cardinality (one-to-one, one-to-many, or many-to-many) and optionality (whether the relationship is mandatory or optional). The conceptual model gradually evolves through multiple review cycles with stakeholders, incorporating feedback and adjustments to ensure comprehensive coverage of business needs. This iterative approach helps identify missing entities, clarify ambiguous relationships, and validate that the model supports all identified use cases.

Logical Data Models: Defining the Structure

Logical data models bridge the gap between conceptual understanding and physical implementation, translating business-focused concepts into structured database designs. This modeling level introduces technical considerations while remaining independent of specific database management systems. The logical model refines the conceptual model by adding detailed attribute definitions, specifying data types, establishing primary and foreign keys, and normalizing the structure to eliminate redundancy. Database designers use logical models to ensure data integrity, optimize storage efficiency, and establish clear relationships that support complex queries and transactions.

The logical modeling process involves applying normalization principles to create an efficient and maintainable database structure. This includes identifying functional dependencies between attributes, eliminating repeating groups, and ensuring that each piece of information is stored in exactly one place. The logical model also defines domains for attributes, specifying valid value ranges, formats, and constraints that ensure data quality. By addressing these concerns at the logical level, designers create a robust foundation that can be adapted to various physical implementations while maintaining consistency and integrity.

Translating Conceptual Models into a Logical Schema

The translation from conceptual to logical schema requires systematic application of data modeling principles and database design patterns. Each entity from the conceptual model becomes a table in the logical schema, with attributes mapped to columns with specific data types and constraints. Relationships identified in the conceptual model are implemented through foreign key constraints, with many-to-many relationships resolved through the introduction of junction tables. This translation process must consider performance implications, balancing normalization benefits against the potential need for denormalization to support specific query patterns or reporting requirements.

During the translation process, designers must make critical decisions about data types, key selection, and constraint implementation. Natural keys from the business domain may be supplemented or replaced with surrogate keys for performance and flexibility. Composite attributes from the conceptual model might be decomposed into atomic values, while derived attributes may be excluded from storage in favor of runtime calculation. The logical schema must also address temporal aspects of data, determining how historical information will be tracked and whether audit trails are required for compliance or business intelligence purposes.

Physical Data Models: The Implementation Blueprint

Physical data models represent the actual implementation of the database structure within a specific database management system. This modeling level incorporates platform-specific features, optimization techniques, and storage considerations that directly impact system performance and scalability. The physical model translates logical designs into concrete database objects, including tables, indexes, views, stored procedures, and triggers. Database administrators use physical models to optimize storage allocation, implement partitioning strategies, and configure security settings that protect sensitive data while enabling appropriate access for authorized users.

What Role Does the Physical Schema Play in Database Management?

The physical schema serves as the definitive specification for database implementation, determining how data is actually stored on disk and accessed by applications. This schema level directly impacts system performance through decisions about index placement, partition strategies, and storage parameters. Database management systems use the physical schema to optimize query execution plans, allocate storage resources, and manage concurrent access to data. The physical implementation must balance competing requirements for query performance, storage efficiency, and maintenance overhead, making trade-offs that align with specific application needs and usage patterns.

Physical schema management encompasses ongoing optimization and maintenance activities that ensure continued system performance as data volumes grow and usage patterns evolve. This includes monitoring index usage and effectiveness, adjusting partition boundaries, and implementing compression strategies for large tables. Database administrators must regularly analyze query performance, identify bottlenecks, and modify the physical schema to address performance issues. The physical schema also plays a crucial role in backup and recovery strategies, determining how data can be efficiently backed up and quickly restored in case of system failures.

Key Considerations for Physical Schema Design

Physical schema design requires careful consideration of hardware capabilities, expected data volumes, and usage patterns to create an optimized database structure. Storage requirements must account not only for current data volumes but also for projected growth, ensuring that the database can scale effectively over time. The selection of appropriate storage engines, file organizations, and compression techniques significantly impacts both performance and storage efficiency. Database designers must understand the characteristics of different storage technologies, including traditional hard drives, solid-state drives, and in-memory storage options, to make informed decisions about data placement and access strategies.

Indexing Strategies for Performance

Effective indexing strategies form the cornerstone of database performance optimization, dramatically reducing query execution times for frequently accessed data. The selection of appropriate indexes requires analysis of query patterns, understanding which columns are commonly used in WHERE clauses, JOIN conditions, and ORDER BY statements. While indexes accelerate read operations, they introduce overhead for write operations, as the database must maintain index structures during inserts, updates, and deletes. Database designers must carefully balance the benefits of improved query performance against the costs of index maintenance, selecting indexes that provide maximum benefit for critical operations.

Advanced indexing techniques extend beyond simple single-column indexes to include composite indexes, covering indexes, and specialized index types for specific data patterns. Composite indexes support queries that filter or sort by multiple columns, while covering indexes include all columns needed by a query, eliminating the need to access the underlying table. Specialized index types such as full-text indexes for text searching, spatial indexes for geographic data, and bitmap indexes for low-cardinality columns provide optimized access paths for specific query types. The physical schema must also consider index fragmentation and maintenance requirements, establishing regular maintenance routines to ensure indexes remain efficient over time.

Partitioning Large Tables

Table partitioning divides large tables into smaller, more manageable segments that can be accessed and maintained independently. This technique improves query performance by allowing the database to eliminate irrelevant partitions from query execution plans, reducing the amount of data that must be scanned. Partitioning also facilitates maintenance operations such as archiving old data, as entire partitions can be quickly dropped or moved to archival storage. The selection of partition keys and boundaries requires careful analysis of data distribution and access patterns to ensure that partitions effectively support common query patterns.

Vertical vs. Horizontal Partitioning

Horizontal partitioning divides tables by rows, distributing records across multiple partitions based on partition key values such as date ranges, geographic regions, or customer segments. This approach works well for time-series data where queries typically access recent data more frequently than historical records. Horizontal partitioning enables parallel processing of queries that span multiple partitions and facilitates data lifecycle management by allowing old partitions to be archived or purged according to retention policies. The partition strategy must ensure even data distribution to prevent hotspots that could create performance bottlenecks.

Vertical partitioning splits tables by columns, separating frequently accessed columns from those accessed less often. This technique reduces the amount of data read during queries that only need a subset of columns, improving cache efficiency and reducing I/O overhead. Vertical partitioning is particularly effective for tables with many columns where different access patterns exist for different column groups. However, queries that need data from multiple vertical partitions may require joins, potentially offsetting performance benefits. The physical schema must carefully evaluate access patterns to determine when vertical partitioning provides net performance improvements.

Exploring Different Types of Schema Architecture

Relational Schema (Relational Model)

The relational model remains the dominant paradigm for database organization, providing a mathematical foundation for data management based on set theory and predicate logic. Relational schemas organize data into tables with well-defined relationships, ensuring data consistency through normalization and referential integrity constraints. This model's strength lies in its ability to handle complex queries through SQL, supporting ad-hoc queries and complex joins that would be difficult or impossible in other database models. The relational approach provides ACID (Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, Durability) properties that guarantee reliable transaction processing, making it ideal for applications requiring strict data consistency.

Modern relational database systems have evolved to incorporate features that address traditional limitations while maintaining the core benefits of the relational model. These enhancements include support for JSON data types that enable semi-structured data storage, advanced indexing techniques that optimize complex query patterns, and in-memory processing capabilities that dramatically improve performance for analytical workloads. The relational model's maturity means extensive tooling support, widespread expertise, and proven design patterns that reduce implementation risk and accelerate development timelines.

When to Use a Relational Database Structure

Relational database structures excel in scenarios requiring complex relationships between entities, strict data consistency, and sophisticated query capabilities. Financial systems, enterprise resource planning applications, and customer relationship management systems typically rely on relational databases due to their transactional integrity and ability to maintain complex business rules. The relational model's support for ACID transactions ensures that critical business operations such as financial transfers, inventory updates, and order processing maintain consistency even in the face of system failures or concurrent access. Applications that require complex reporting and ad-hoc query capabilities benefit from SQL's expressive power and the query optimization capabilities of modern relational database management systems.

Star Schema: Optimized for Analytics

The star schema represents a specialized database structure designed specifically for analytical processing and business intelligence applications. This schema architecture organizes data into a central fact table surrounded by dimension tables, creating a star-like pattern when visualized. The simplicity of the star schema makes it intuitive for business users to understand and enables efficient query processing for analytical workloads. By denormalizing dimension data and pre-aggregating facts, star schemas optimize query performance for the complex aggregations and dimensional analysis common in business intelligence applications.

What are the benefits of a Star Schema data model?

Star schemas provide numerous advantages for analytical processing, including simplified query construction, improved query performance, and intuitive data navigation. The denormalized structure of dimension tables eliminates the need for complex joins when filtering or grouping data, reducing query complexity and improving performance. Query optimizers can efficiently process star schema queries using specialized techniques such as star join optimization, which leverages the schema's predictable structure. Business users find star schemas easier to understand and navigate, as the clear separation between facts and dimensions aligns with how they conceptualize business metrics and analysis dimensions.

The star schema's design facilitates incremental data loading and historical tracking through slowly changing dimension techniques. This enables organizations to maintain historical context for their analytical data, supporting trend analysis and time-based comparisons. The schema's modular structure also simplifies maintenance and enhancement, as new dimensions or facts can be added without disrupting existing analytical processes. Performance predictability makes capacity planning more straightforward, as the impact of data growth on query performance follows well-understood patterns.

Understanding Fact and Dimension Tables

Fact tables store quantitative data about business events or transactions, containing metrics that users want to analyze and aggregate. These tables typically include foreign keys to dimension tables and numeric measures such as sales amounts, quantities, or durations. Fact tables often contain millions or billions of rows, representing the detailed transactional history of the business. The grain of the fact table, which defines the level of detail stored, must be carefully chosen to balance storage requirements with analytical needs. Additive measures that can be summed across all dimensions provide the most flexibility, while semi-additive and non-additive measures require special handling during aggregation.

Dimension tables provide descriptive context for the facts, containing attributes that users use to filter, group, and label their analyses. These tables typically contain far fewer rows than fact tables but include many descriptive columns that support various analytical perspectives. Dimension tables often include hierarchical relationships that enable drill-down and roll-up operations, such as product categories and subcategories or geographic hierarchies from country to city. The denormalized structure of dimension tables in star schemas trades storage space for query simplicity and performance, eliminating the need for multiple joins when accessing descriptive attributes.

Snowflake Schema: An Extension of the Star Schema

The snowflake schema extends the star schema concept by normalizing dimension tables into multiple related tables, creating a more complex structure that resembles a snowflake pattern. This normalization reduces data redundancy and storage requirements, particularly beneficial when dimension tables contain many attributes or when certain attributes are shared across multiple dimensions. The snowflake schema maintains referential integrity more strictly than star schemas, ensuring consistency when dimension attributes are updated. This approach suits organizations with complex dimensional hierarchies or those requiring strict data governance and reduced storage footprint.

How does a Snowflake Schema differ from a Star Schema?

The primary difference between snowflake and star schemas lies in the normalization of dimension tables. While star schemas maintain denormalized dimension tables for query performance, snowflake schemas normalize these tables to eliminate redundancy. This normalization creates additional tables and relationships, increasing query complexity as more joins are required to retrieve dimension attributes. The trade-off between storage efficiency and query performance must be carefully evaluated based on specific requirements. Snowflake schemas may be appropriate when storage costs are a primary concern, when dimension updates are frequent, or when maintaining strict data consistency across shared dimensional attributes is critical.

Flat Model Schema: Simplicity and Its Downsides

Flat model schemas represent the simplest form of data organization, storing all information in a single table or a minimal number of tables with little to no normalization. This approach mirrors spreadsheet-like structures familiar to many business users, making data immediately accessible without complex joins or relationships. Flat schemas can be appropriate for simple applications, data staging areas, or scenarios where the data structure is truly flat without meaningful relationships. The simplicity of flat schemas enables rapid prototyping and reduces the initial complexity of data loading and access.

However, flat schemas introduce significant challenges as data volumes and complexity grow. The lack of normalization leads to extensive data redundancy, increasing storage requirements and creating consistency challenges when updates are required. Without proper relationship modeling, flat schemas cannot efficiently represent complex business entities and their interactions. Query performance degrades as table sizes grow, particularly for operations that would benefit from selective access to specific attributes. The absence of referential integrity constraints increases the risk of data quality issues, as there are no database-level controls to prevent invalid or inconsistent data entry.

Practical Steps to Effective Schema Management

What are the Best Practices for DB Schema Design?

Effective database schema design follows established best practices that ensure scalability, maintainability, and performance throughout the system lifecycle. The design process should begin with thorough requirements analysis, understanding both current needs and anticipated future growth. Iterative design approaches allow for refinement based on prototype testing and stakeholder feedback, ensuring the final schema meets all business requirements. Documentation plays a crucial role in schema management, providing clear explanations of design decisions, business rules implementation, and relationship rationale. Version control systems should track schema changes, enabling rollback capabilities and providing an audit trail of schema evolution.

Performance considerations must be integrated into the design process from the beginning rather than treated as an afterthought. This includes planning for appropriate indexes, considering partitioning strategies for large tables, and evaluating denormalization opportunities where query performance requirements justify controlled redundancy. The schema should incorporate flexibility for future enhancements while maintaining backward compatibility with existing applications. Regular review and optimization of the schema ensure continued alignment with evolving business needs and technological capabilities.

Normalization: Minimizing Data Redundancy

Database normalization systematically organizes data to minimize redundancy and dependency, improving data integrity and reducing storage requirements. The normalization process applies a series of rules (normal forms) that progressively eliminate different types of redundancy and dependency. While higher levels of normalization generally improve data consistency and reduce update anomalies, they may also increase query complexity and impact performance. Database designers must balance normalization benefits against practical performance requirements, sometimes deliberately denormalizing certain structures to optimize critical operations.

First Normal Form (1NF)

First Normal Form establishes the foundation for relational database design by requiring that each table cell contains only atomic (indivisible) values and that each record is unique. This eliminates repeating groups and multi-valued attributes that complicate data manipulation and querying. Achieving 1NF often involves decomposing complex attributes into separate columns or creating additional tables to handle one-to-many relationships properly. For example, instead of storing multiple phone numbers in a single field, 1NF requires either separate columns for each phone type or a separate phone numbers table linked by a foreign key.

Second Normal Form (2NF)

Second Normal Form builds upon 1NF by eliminating partial dependencies, ensuring that all non-key attributes depend on the entire primary key rather than just part of it. This requirement is particularly relevant for tables with composite primary keys, where some attributes might depend on only one component of the key. Achieving 2NF typically involves decomposing tables to separate attributes that depend on different key components. This normalization level reduces update anomalies and ensures that each piece of information is stored in the most appropriate location within the database structure.

Third Normal Form (3NF)

Third Normal Form eliminates transitive dependencies, ensuring that non-key attributes depend directly on the primary key rather than on other non-key attributes. This prevents update anomalies that can occur when changing one non-key attribute requires updates to other related attributes. Achieving 3NF often involves creating separate tables for groups of related attributes that form logical entities. For most transactional systems, 3NF provides an optimal balance between data integrity and query performance, eliminating most redundancy while maintaining reasonable query complexity.

Boyce-Codd Normal Form (BCNF)

Boyce-Codd Normal Form represents a stronger version of 3NF that addresses certain anomalies that can still exist in 3NF tables. BCNF requires that every determinant (attribute or set of attributes that determines other attributes) be a candidate key. This eliminates all redundancy based on functional dependencies, providing the highest level of normalization for most practical purposes. While BCNF provides excellent data integrity, the additional decomposition required may create performance challenges for complex queries, making it most suitable for systems where data integrity is paramount and query patterns are well-understood.

Choosing the Right Data Types

Selecting appropriate data types significantly impacts storage efficiency, query performance, and data integrity within the database system. Each data type carries specific storage requirements and processing characteristics that affect overall system performance. Oversized data types waste storage space and memory, reducing cache efficiency and increasing I/O operations. Undersized types risk data truncation or overflow errors. The choice between fixed and variable-length types affects storage patterns and performance characteristics, with fixed-length types providing predictable storage and access patterns while variable-length types optimize storage for varying data sizes.

Naming Conventions and Documentation

Consistent naming conventions create self-documenting database structures that improve maintainability and reduce errors during development and maintenance. Naming standards should cover all database objects including tables, columns, indexes, constraints, and stored procedures. Clear, descriptive names that reflect business terminology while following technical best practices help bridge the gap between business requirements and technical implementation. Documentation should capture not only what the schema contains but why specific design decisions were made, providing context for future modifications and troubleshooting.

How Can You Visualize a Database Layout?

Database visualization tools transform complex schema structures into intuitive diagrams that facilitate understanding and communication among stakeholders. These visualizations range from high-level conceptual diagrams suitable for business discussions to detailed physical diagrams used for implementation and troubleshooting. Modern visualization tools offer interactive features that allow users to explore relationships, filter views to focus on specific areas, and generate documentation automatically from the database metadata. Effective visualization helps identify design issues, optimize relationships, and communicate the database structure to team members with varying technical backgrounds.

The Role of Entity-Relationship Diagrams (ERDs) in DB Design

Entity-Relationship Diagrams serve as the primary visualization tool for database design, providing a standardized notation for representing entities, attributes, and relationships. ERDs support multiple levels of detail, from conceptual models that focus on business entities to physical models that include implementation details such as data types and indexes. The visual nature of ERDs makes them invaluable for design reviews, enabling stakeholders to quickly identify missing relationships, incorrect cardinalities, or potential performance issues. Modern ERD tools integrate with database management systems, allowing bidirectional synchronization between diagrams and actual database schemas, ensuring documentation remains current as the database evolves.

Schema Management in SQL vs. NoSQL Databases

Schema management approaches differ fundamentally between SQL and NoSQL databases, reflecting their distinct design philosophies and use cases. SQL databases enforce rigid schemas that must be defined before data insertion, providing strong consistency guarantees and data validation at the database level. This approach ensures data integrity but requires careful planning and may necessitate schema migrations when requirements change. NoSQL databases often adopt flexible schema approaches, allowing documents or records with varying structures to coexist within the same collection, providing agility for rapidly evolving applications but shifting data validation responsibilities to the application layer.

Schema Definition in SQL Databases

SQL databases require explicit schema definition through Data Definition Language (DDL) statements that create and modify database structures. This formal approach ensures that all data conforms to predefined structures, with the database engine enforcing data types, constraints, and relationships. Schema changes in SQL databases typically require careful planning and execution, as modifications can impact existing data and applications. Migration strategies must handle schema versioning, backward compatibility, and data transformation when structural changes affect existing records. Modern SQL databases provide online schema change capabilities that minimize downtime during modifications, but these operations still require careful coordination and testing.

Schema on Read vs. Schema on Write in NoSQL

NoSQL databases often implement a schema-on-read approach, where data structure is interpreted when accessed rather than enforced during storage. This flexibility allows applications to evolve rapidly without formal schema migrations, as new fields can be added to documents without affecting existing records. However, this flexibility transfers complexity to the application layer, which must handle variations in document structure and ensure data consistency. Some NoSQL systems offer optional schema validation that provides a middle ground, allowing developers to enforce structure when needed while maintaining flexibility where appropriate. The choice between schema-on-read and schema-on-write approaches depends on specific application requirements, balancing flexibility against consistency needs.

Advanced Topics in Database Organization

What is Schema Evolution and Why is it Important?

Schema evolution represents the ongoing process of modifying database structures to accommodate changing business requirements, technological advances, and performance optimization needs. As organizations grow and adapt, their data models must evolve to support new features, integrate with additional systems, and handle increasing data volumes. Effective schema evolution maintains system stability while enabling innovation, requiring careful planning to minimize disruption to existing applications and processes. The ability to evolve schemas gracefully determines whether database systems can adapt to changing requirements or become technical debt that constrains business agility.

The importance of schema evolution extends beyond technical considerations to impact business competitiveness and operational efficiency. Organizations that master schema evolution can rapidly deploy new features, integrate emerging data sources, and optimize performance without costly system replacements. Effective evolution strategies consider not only the immediate changes required but also the long-term trajectory of the system, building flexibility into the schema design that accommodates anticipated future modifications. This forward-thinking approach reduces the cost and risk of changes while maintaining system reliability and performance throughout the evolution process.

Techniques for Managing Schema Changes

Managing schema changes requires systematic approaches that ensure consistency, minimize downtime, and maintain data integrity throughout the modification process. Version control systems track schema changes alongside application code, enabling coordinated deployments and rollback capabilities when issues arise. Migration scripts automate the transformation of existing data to conform to new structures, reducing manual effort and ensuring consistency across environments. Database refactoring techniques apply incremental changes that gradually transform the schema while maintaining compatibility with existing applications, allowing for phased transitions that reduce risk.

Advanced schema management techniques include blue-green deployments that maintain parallel schema versions during transitions, enabling instant rollback if issues emerge. Feature flags allow applications to adapt to schema changes dynamically, supporting gradual rollouts and A/B testing of new structures. Database abstraction layers provide flexibility by decoupling application logic from physical schema details, allowing schema modifications without extensive application changes. These techniques require investment in tooling and processes but provide significant benefits for organizations managing complex database systems with high availability requirements.

Forward and Backward Compatibility

Forward compatibility ensures that older versions of applications can work with newer schema versions, while backward compatibility allows newer applications to function with older schemas. Achieving bidirectional compatibility requires careful design of schema changes, avoiding modifications that break existing functionality while enabling new capabilities. Techniques such as adding nullable columns, creating new tables rather than modifying existing ones, and maintaining deprecated fields during transition periods help preserve compatibility. This approach enables rolling deployments and reduces the coordination required between database and application updates.

Compatibility strategies must balance the benefits of clean schema design against the practical needs of system evolution. While maintaining multiple versions of schema elements increases complexity and storage overhead, it provides crucial flexibility during transitions. Organizations must establish clear deprecation policies that specify how long compatibility will be maintained and communicate these timelines to all stakeholders. Automated testing that validates compatibility across version combinations helps identify potential issues before they impact production systems, ensuring smooth transitions as schemas evolve.

How Does Database Framework Impact Schema Design?

The choice of database framework significantly influences schema design decisions, as different frameworks offer varying capabilities, constraints, and optimization opportunities. Traditional relational database management systems provide rich feature sets for complex schema definitions, including sophisticated constraint mechanisms, trigger capabilities, and stored procedure support. These frameworks excel at maintaining data integrity and supporting complex transactional processing but may require more rigid schema definitions. Modern NewSQL databases attempt to combine the scalability of NoSQL systems with the ACID guarantees of traditional relational databases, influencing schema design toward distributed architectures that can scale horizontally while maintaining consistency.

NoSQL frameworks fundamentally alter schema design approaches by relaxing traditional constraints in favor of scalability and flexibility. Document databases encourage denormalized designs that embed related data within documents, reducing the need for joins but potentially increasing data redundancy. Graph databases model relationships as first-class citizens, requiring schema designs that emphasize connections over traditional table structures. Column-family stores optimize for write-heavy workloads and time-series data, influencing schema designs toward wide, sparse tables with dynamic column creation. Understanding framework characteristics enables designers to create schemas that leverage platform strengths while mitigating limitations.

Cloud-native database frameworks introduce additional considerations for schema design, including multi-tenancy support, automatic scaling capabilities, and managed service constraints. Serverless databases require schemas that can efficiently handle variable workloads and automatic scaling events without performance degradation. Multi-region deployment capabilities influence schema design toward eventual consistency models and conflict resolution strategies. The economic model of cloud databases, where costs directly correlate with resource consumption, encourages schema optimization for storage efficiency and query performance. These frameworks often provide built-in features for common patterns such as audit logging, soft deletes, and temporal data management, allowing simpler schema designs that leverage platform capabilities.

Frequently Asked Questions about Schema Design

How do you design a database schema for a large database system?

Designing schemas for large database systems requires a comprehensive approach that addresses scalability, performance, and maintainability from the outset. The process begins with thorough capacity planning, estimating data volumes, transaction rates, and query patterns to inform design decisions. Large systems typically benefit from modular schema designs that separate concerns into distinct functional areas, enabling independent scaling and optimization of different components. Partitioning strategies must be incorporated early in the design process, as retrofitting partitioning into existing large tables can be extremely challenging. The schema should anticipate growth patterns and include mechanisms for archiving historical data, preventing unbounded table growth that could impact performance.

Performance optimization for large database systems requires careful attention to indexing strategies, query patterns, and data access paths. The schema design should minimize expensive operations such as large table scans and complex joins across massive datasets. Denormalization may be necessary for frequently accessed data combinations, trading storage space for query performance. Materialized views and summary tables can pre-aggregate data for common analytical queries, reducing the computational burden during query execution. The schema should also consider read-write separation, potentially maintaining different structures optimized for transactional processing versus analytical queries.

Operational considerations become critical in large database systems, requiring schemas that support online maintenance, incremental backups, and disaster recovery procedures. The design should facilitate parallel processing for both queries and maintenance operations, enabling efficient use of available hardware resources. Monitoring and diagnostics capabilities should be built into the schema design, including audit tables, performance metrics collection, and query logging structures. Large systems often require sophisticated security models implemented at the schema level, including row-level security, data encryption, and comprehensive access control mechanisms that protect sensitive information while enabling appropriate data access.

Can you modify a database schema after it has been created?

Database schemas can and often must be modified after creation to accommodate evolving business requirements, performance optimization needs, and bug fixes. Modern database management systems provide ALTER statements that enable various schema modifications, including adding or dropping columns, modifying data types, creating or removing indexes, and adjusting constraints. However, schema modifications on production systems require careful planning and execution to minimize disruption and maintain data integrity. The complexity of schema modifications varies significantly depending on the type of change, the size of affected tables, and the database system's capabilities for online schema changes.

The ability to modify schemas safely depends on several factors, including the database system's support for online DDL operations, the availability of maintenance windows, and the impact on dependent applications. Some modifications, such as adding nullable columns or creating new indexes, can often be performed with minimal impact on running systems. Other changes, such as modifying column data types or dropping columns, may require table rebuilds that lock tables for extended periods. Modern database systems increasingly support online schema changes that allow modifications while maintaining table availability, though these operations may impact performance during execution.

Best practices for schema modification include thorough testing in non-production environments, maintaining rollback scripts for every change, and implementing changes during low-usage periods when possible. Schema versioning systems help track modifications and ensure consistency across multiple environments. When modifications affect application code, coordination between database and application deployments becomes critical. Some organizations implement expand-contract patterns, where schema changes are deployed in phases that maintain compatibility throughout the transition. This approach first expands the schema to support both old and new structures, migrates applications to use the new structure, and finally contracts the schema by removing deprecated elements.

What tools are used for schema organization and data modeling?

Professional data modeling tools provide comprehensive environments for designing, documenting, and managing database schemas throughout their lifecycle. Enterprise tools like ERwin Data Modeler, IBM InfoSphere Data Architect, and Oracle SQL Developer Data Modeler offer sophisticated features for creating conceptual, logical, and physical models with support for multiple database platforms. These tools enable forward and reverse engineering, allowing designers to generate schemas from models or create models from existing databases. Advanced features include impact analysis for proposed changes, data lineage tracking, and integration with metadata repositories that maintain enterprise-wide data definitions.

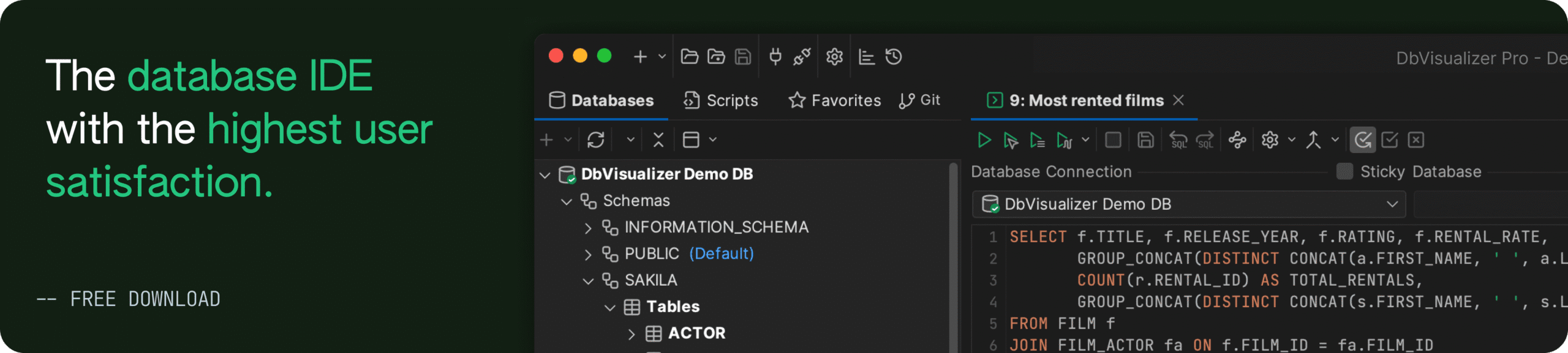

Open-source and lightweight alternatives provide accessible options for smaller teams and projects, with tools like MySQL Workbench, pgModeler for PostgreSQL, and DBeaver offering robust modeling capabilities without enterprise licensing costs. These tools typically focus on specific database platforms but provide essential features for schema design, visualization, and documentation. Web-based modeling tools such as dbdiagram.io and DrawSQL enable collaborative schema design without software installation, facilitating remote team collaboration and rapid prototyping. These platforms often integrate with version control systems and documentation platforms, supporting modern development workflows.

Specialized tools address specific aspects of schema management and data modeling, complementing general-purpose modeling applications. Schema comparison tools identify differences between database environments, facilitating synchronization and deployment processes. Performance analysis tools examine schema structures to identify optimization opportunities, suggesting index improvements and highlighting potential bottlenecks. Data profiling tools analyze existing data to understand patterns and distributions that inform schema design decisions. Documentation generators create comprehensive schema documentation from database metadata, ensuring that technical documentation remains synchronized with actual implementations. Version control integration tools manage schema definitions alongside application code, enabling coordinated deployments and maintaining change history.

Modern development practices increasingly incorporate schema management into continuous integration and deployment pipelines, requiring tools that support automation and scripting. Migration frameworks like Flyway and Liquibase manage schema versions and automate deployment processes, ensuring consistency across development, testing, and production environments. Infrastructure-as-code approaches treat schema definitions as code artifacts, using tools like Terraform to manage database infrastructure alongside schema definitions. These automated approaches reduce manual effort, minimize human error, and provide audit trails for compliance requirements.

The selection of appropriate tools depends on various factors including team size, budget constraints, database platforms, and integration requirements with existing development toolchains. Organizations should evaluate tools based on their support for required database systems, collaboration features for distributed teams, integration capabilities with existing tools, and scalability to handle growing schema complexity. Training requirements and learning curves also influence tool selection, as complex enterprise tools may require significant investment in user training to realize their full benefits. The evolution toward cloud-based and collaborative tools reflects broader industry trends toward distributed development teams and agile methodologies that require rapid iteration and continuous deployment capabilities.